Ngāti Apa trace their earliest connection to Lake Rotoiti (small waters) from their ancestor Kupe. According to Ngāti Apa tradition, Rotoiti and Rotoroa are the eye-sockets of Te Wheke-a-Muturangi, which Kupe chased across the Pacific, eventually slaying it at the entrance to Kura Te Au (Tory Channel) and plucking out its eyes.

Together, Rotoiti and Rotoroa are the source of five important waterways — the Kawatiri, Motueka, Motupiko, Waiau-toa and Awatere rivers — and served as the central terminus of a series of well-known and well-used tracks (“the footprints of the tīpuna”) linking Kurahaupō communities in the Wairau, Waiau-toa (Clarence River), Kaituna, Whakatū, Te Tai o Aorere (Tasman Bay), Mohua (Golden Bay) and the Kawatiri district.

A Ngāti Apa pepeha relating to the lakes illustrates the iwi’s connection with the area and Kehu:

Ko Kehu te maunga

Ko Kawatiri te awa

Ko Rotoroa me Rotoiti ngā roto

Ko Ngāti Apa ki te Rā Tō te iwi

Ko Kehu te tangata

The lakes area was a rich mahinga kai, including birds (kiwi, South Island kōkako, piopio, pīwauwau (bush wren) and whio (blue duck), kiore, tuna (eels), inanga, fern root and the root of the tī kōuka (cabbage tree), and berries of the miro, tawa, kahikatea and tōtara.

But it is the shrub neinei that is of particular significance. Only found in the lakes area, neinei was — and still is — highly valued by Ngāti Apa as a material to make korowai.

Pahi found in this area are another reflection of the unique identity of Ngāti Apa ki te Rā Tō. Pahi, or huts, constructed by Ngāti Apa were of a distinctive design, and served as both seasonal and more permanent shelter.

The four small alpine tarns of Paratītahi and the larger tarn Paraumu were important means of demonstrating identity, authority and mana within Ngāti Apa communities, contributing to social organisation and stability within the iwi. Young ariki were traditionally taken to these tarns in summer months, where they would be ritually cleansed in the waters before being presented to their people.

The four small alpine tarns of Paratītahi and the larger tarn Paraumu were important means of demonstrating identity, authority and mana within Ngāti Apa communities, contributing to social organisation and stability within the iwi. Young ariki were traditionally taken to these tarns in summer months, where they would be ritually cleansed in the waters before being presented to their people.

Rotomaninitua (Lake Angelus) is one of several markers and resting places on the pathway of deceased Ngāti Apa as they make their journey to the West Coast and on to Hawaiki.

Rotopōhueroa (“the long calabash”) is another key landmark for the iwi. Named and discovered by Ngāti Apa tīpuna, it was traditionally used for hauhunga (bone cleansing) ceremonies involving deceased females. As with the bones of males, the cleansed bones were later deposited in Te Kai ki o Maruia (the Sabine Valley).

Once the bones had been washed, the spirits were released and they would journey from Rotopōhueroa along the West Coast and Te Taitapu (the sacred pathway) to Te One Tahua (Farewell Spit), Te Rēinga and then to Hawaiki.

The name “Rotopōhueroa” evokes the calabash as a receptacle for the placenta (whenua), giving Rotopōhueroa further significance within Ngāti Apa cosmology and beliefs.

Rotomairewhenua, or “the lake of peaceful lands,” holds great significance for Ngāti Apa ki te Rā Tō. Discovered and named by Ngāti Apa tīpuna, the lake was one of a number of lakes and tarns used as markers on a series of interwoven trails used by the iwi over many centuries while travelling from one part of the rohe to another.

Known as the clearest body of fresh water in the world, Rotomairewhenua was traditionally where hauhanga (bone cleansing) ceremonies were carried out by Ngāti Apa for the bones of deceased males. Once washed, the cleansed bones were deposited in Te Kai ki o Maruia (the Sabine Valley).

Rotomairewhenua is fed by an underground river from Rotopōhueroa, illustrating for Ngāti Apa the interconnectedness of the natural world. According to our tīpuna, once the bones had been washed, the spirits were released and would journey from Rotomairewhenua along the West Coast and Te Taitapu (the sacred pathway) to Te One Tahua (Farewell Spit), Te Rēinga and, ultimately, Hawaiki.

Ngāti Apa trace their earliest connections to Lake Rotoroa (large waters) from their ancestor Kupe – according to Ngāti Apa ki te Rā Tō pūrākau, Rotoiti and Rotoroa are the eye sockets of the taniwha Te Wheke-a-Muturangi.

This area formed the central hub of a series of well-known and well-used trails linking Ngāti Apa to communities in the Wairau, Waiau-toa (Clarence River), Kaituna, Whakatū, Tasman Bay, Mohua (Golden Bay) and the Kawatiri district.

Later, the region was used as a refuge for the tribe during the northern invasions and formed a secure base for warriors who continued to defend their rohe, particularly in the Whakatū area.

A rich mahinga kai, including birds, kiore, inanga and tuna, Rotoroa was also the site of extensive and well-established fern gardens, or tawaha, planted by our tīpuna high on the northern slopes above Rotoroa. This provided a good source of aruhe or fern-root, a staple food until the introduction of the potato.

The gardens were described by European visitors to the region in the 1840s and are still visible today.

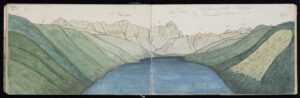

Illustration by Johann Franz Julius von Haast of extensive fern cultivations (light foreground) at Rotoroa, 1860. Haast, Johann Franz Julius von, 1822-1887. Haast, Johann Franz Julius von, 1822-1887: Rotoroa, Mount MacKay, Humbold Chaine. 25 Januar 1860. Haast family: Collection. Ref: A-108-034. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. /records/22680353

Ethnographer Elsdon Best noted in 1902 that aruhe from these inland areas was much better than that harvested from the coast. Before it could be eaten, aruhe required a lot of preparation and was often mixed with plant extracts and additives to make both sweet and savoury dishes.

In the Ngāti Apa ki te Rā Tō Deed of Settlement there is a clause that recognises our unique connection to both Rotoroa and Rotoiti and the tuna within, and allows us to harvest tuna for special cultural hui.

This short film by Keelan Walker documents whānau as they embark on their annual customary tuna harvest from at Rotoroa.

Mahinga Kai, Ngā Roto | Lakes, Te Taiao, Wāhi Tapu

Ngā Roto | Lakes, Wāhi Tapu

Ngā Roto | Lakes, Wāhi Tapu

Ngā Roto | Lakes, Wāhi Tapu

Ngā Roto | Lakes, Wāhi Tapu

Ngā Roto | Lakes, Wāhi Tapu

Mahinga Kai, Ngā Roto | Lakes, Te Taiao, Wāhi Tapu